|

||||||||||

| HOME >Spring 2009 - Volume 53 - Number 2 | ||||||||||

Arts-Based Group Therapy for Children Who Have Witnessed Domestic Violence Abstract Introduction There are many definitions that encompass domestic violence. In this paper, domestic violence that children witness will be defined as: Hearing an episode of violence (Gerwitz and Edleson, 2004; Groves, 1999; Margolin and Gordis, 2000) Problem and Significance Children are affected by domestic violence in many forms. The violence can be experienced by witnessing it, hearing it, and also getting caught in the middle of it.

The significance this holds for our future adults is not a positive one. The children who are affected by domestic violence eventually mix with other children, usually starting at school-age. The children who have witnessed domestic violence have a greater possibility of poor coping skills, mental health problems and problems with empathy. How witnessing domestic violence shapes the affected child's life can manifest itself by school problems, trouble connecting with other people, anger management issues, and the inability to have compassion for others. Figure 1 - Effects of Children Who Witness Domestic Violence

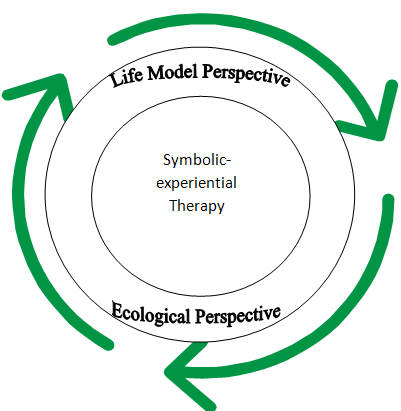

Focus The focus of this paper is to create a holistic treatment method for professionals to use with children who have been affected by domestic violence. This will be done by combining sections of the life model with symbolic-experiential therapy in a therapeutic group setting for children. The group therapy framework will be based on the medicine wheel. Basic Assumptions / Rationale The heart of the therapy group will be art therapy. “Art therapy and play therapy are two popular forms of treatment with children from violent homes.” (Gil, 1991; Klorer, 2000; Malchiodi, 1997; Webb, 2007). By combining art therapy within a group setting, this can provide an age appropriate, therapeutic setting along with their peers. “Groupwork reduces isolation, promotes corrective emotional experiences, and enhances interpersonal skills.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 252) By reducing isolation of the children, encouraging positive emotional experiences and improving their interpersonal skills, it can lead to more positive self worth and esteem, and knowledge on how to positively deal with their experiences together. The rationale behind combining the Life Model with symbolic-experiential therapy is to assist children in understanding the world they live in and how it affects different systems. For example, children can learn about person:environment fit. This knowledge can expand a child's world and they can further understand the effect they have on systems around them. If we further symbolize the child's experiences to domestic violence by using art therapy; the child can then safely work through the trauma without internalization of feelings linked to past traumas. “The symbolic-experiential model of family therapy evolved primarily from the personhood of Carl Whitaker.” (Mitten, Connell and Bumberry, 1999, p. 25) “The children he worked with early in his career captured his heart and engaged him in a world of fantasy from which he never emerged. From this experience, he became aware of the power of play and the creative unconscious, which he relied on throughout his career to lower defenses and access primary process relating.” (Mitten, Connell and Bumberry, 1999, p. 23) Combining the Life Model with Symbolic-Experiential Therapy In order to create all-inclusive content for a therapeutic group of children who are affected by domestic violence, I will use Whittaker's (Connell, Mitten and Whittaker, 1993) symbolic-experiential therapy he used with families and apply relevant pieces of the Life Model of social work practice. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) I will also apply certain areas of the ecological perspective (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) to further round out the content to cover all physical, emotional, spiritual and mental areas of the participants in the therapeutic group. Figure 2 - Group Therapy Content for Children Affected by Domestic Violence Green arrows represent wrapping both perspectives in the therapeutic process.

(Germain and Gitterman, 2005; Mitten, Connell and Bumberry, 1999) The Life Model of social work practice is patterned on life processes directed to 1) people's strengths, their innate push toward health, continual growth and release of potential; 2) modifications of environments, as needed, so that they sustain and promote well-being to the maximum degree possible, and 3) raising of the level of person:environment fit for individuals, families, groups and communities. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The life model evolved from the ecological perspective. This makes clear the need to view people and environments as a unitary system within a particular cultural and historical context. Both person and environment can be fully understood only in terms of their relationship, in which each continually influences the other within a particular context. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The original ecological concepts include person:environment fit, adaptations, life stressors, stress, coping measures, relatedness, competence, self esteem, self direction, habitat and niche. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) “Person:environment fit is the actual fit between an individual's or a collective group's needs, rights, goals, and capacities and the qualities and operations of their physical and social environments within particular and historical contexts.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) When children are witnesses to domestic violence, the effect does not stop with just the individual. It passes on through the individual to others. How this child will relate to family members, groups, and communities will be perspective-different because of the trauma they have experienced. According to Jaffe, Wolfe and Wilson (1990), these children have adjustment issues with all aspects of their being, which can include emotional, social, cognitive, physical and behavioural issues. (See Figure 1-Effects of Children Who Witness Domestic Violence) The way the environment is for the child reflects in himself/herself, which then reflects with his/her environment, and continues cyclically. “Adaptations are continuous, change-oriented, cognitive, sensory-perceptual, and behavioural processes people use to sustain or raise the level of fit between themselves and their environment.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) Children who have witnessed domestic violence have experienced trauma. Trauma affects everyone in different ways. “Children who are exposed to family violence may display more fear, anxiety, anger, low self-esteem, excessive worry, and depression than non-exposed children. They may also be more aggressive, oppositional in their behaviour, withdrawn, or lacking in conflict resolution skills, and often have poor peer, sibling and other social relationships.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 250) Children's adaptation skills are continuous, so treatment is needed to raise their level of person:environment fit, after they are no longer exposed to the violence. Life stressors are generated by critical life issues that people perceive as exceeding their personal and environmental resources for handling them. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) A life stressor for children is witnessing domestic violence. “Stress is the internal response to a life stressor and is characterized by troubled emotional or physiological states, or both.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) This internal response is mentioned in the adaptations sections and creates these characteristics. “Repeated exposure to domestic violence is well documented as having numerous negative effects on development and children's mental health.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 250) This is evidenced by the anxiety, anger, low-self esteem, excessive worry and depression these children deal with when exposed to domestic violence. “Coping measures are special behaviours, often novel, that are devised to handle the demands posed by the life stressor.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) There are different ways children can cope with the effects of domestic violence. For some children, it does not seem to affect them at all; with others, it may have a negative effect on them. “Despite exposure to domestic violence, some children are remarkably resilient and show few reactions as a result of their experiences.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 251) Other children develop mental health issues in an attempt to assist themselves in coping with the effects of witnessing the domestic violence. “Children who come from violent homes are diagnosed more frequently with separation anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and conduct disorder than children who are not exposed to family conflicts.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 250) Children who are witnesses to domestic violence have trouble with attachment. According to Malchiodi (2008), children may have attachment difficulties throughout childhood. At the other end of the spectrum, some children may have no boundary setting skills and have the ability to become attached to others too quickly. “The concept of relatedness is based in part on Bowlby's (1973) attachment theory which states that attachment is an innate capacity of human beings.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) Therefore, even though the child's attachment process can be disrupted, there is hope that it can be restored through treatment. White (1959) states, “Competence assumes that all organisms are innately motivated to affect their environment in order to survive.” (as cited in Germain and Gitterman, 2005) This motivation, is termed “effectance”. Accumulated experiences of efficacy lead to a sense of competence. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) Through the group therapy process, the children will be learning how to deal with the trauma they have experienced, expressing feelings, and understanding that violence was not their fault. Through this process, children will gain competence, and positively affect their environment, and vice versa. “Self-esteem is the most important part of self-concept; it represents the extent to which one feels competent, respected, and worthy. Hence, it significantly influences human thinking and behaviour.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) A child's self-esteem can be negatively affected by being exposed to violence, but therapy can help improve the child's self-esteem. The child will be in charge of themselves, expressing their feelings, and learning about the effects of violence. The child will be in a safe learning environment, with children who have something in common with them, and with adults who are skilled in this therapy process. “Self-direction is the capacity to take some degree of control over one's life and to accept responsibility for one's decisions and actions while simultaneously respecting the rights and needs of others. Issues of power and powerlessness are critical to self-direction.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) Children did not have power over the violence they have witnessed. The feelings of powerlessness the children feel is real. The therapy can help them in understanding that the violence was not their fault, and there was nothing they could have done to stop it. The group therapy will help the child achieve a sense of power over their feelings, reactions and decisions in life. This will create competency in the child, and also a sense of relatedness by understanding how their decisions, feeling and reactions can affect those around them. Habitat and niche further delineate the nature of physical and social environments. In ecology, habitat refers to places where the organism can be found, such as nesting places, home ranges and territories. Niche refers to the position occupied by a species within a biotic community – the species place in a web of life. As part of the ecological theory, this can be accomplished by using simplified eco-maps, that include the different individuals, groups and communities the child interacts with on a daily basis. Another area that will be explored is family history. Children that have been witnesses to domestic violence tend to internalize their feelings. With exploring the family history, the children can begin to understand how their parents were raised, any life-changing events or health issues. This can widen their life scope to include those around them and understand how they influence each other. The goal of symbolic-experiential therapy is to enrich, expand and, at times, alter the family's symbolic world. (Connell, Mitten and Whittaker, 1993) “The core variables of symbolic-experiential therapy are a) Generating an Interpersonal Set; b) Creating a Suprasystem; c) Stimulating a Symbolic Context; d) Activating Stress Within the System; e) Creating Symbolic Experience; and f) Moving Out of the System.” (Mitten and Connell, 2004) The first core variable is generating an interpersonal set. (Mitten and Connell, 2004) This can be accomplished by expanding the child's world. Children sometimes blame themselves for things that upset the family system. By expanding the child's world and all of the people, groups and communities that play a part in their life, we can shift the focus of the problem away from them. In doing so, the hope is to have the children realize the domestic violence they have witnessed is not their fault. “In symbolic-experiential therapy, Whittaker shifted the focus from the identified patient to the family system by expanding the system.” (Mitten and Connell, 2004) The core variable has been adapted from a family setting to a group setting. The second core variable is creating a supraystem. (Mitten and Connell, 2004) Parallel play is a component of the second core variable. “Parallel play is one method of establishing a therapeutic alliance in which the family and therapist work side by side. Parallel play involves taking a component of the therapist's life that is analogous to what the patient is discussing and presenting it from another perspective. (Mitten and Connell, 2004) When working with children who have been affected by domestic violence, it is important for the therapist to understand and fully empathize with how the child feels and has experienced a related story. The third variable is stimulating a symbolic context. (Mitten and Connell, 2004) This variable can be accomplished through art therapy. Because of varying degrees of traumatic experiences, it may be more difficult for certain children to express their feelings into words. “When memory cannot be expressed linguistically, it remains at a symbolic level, for which there are no words to describe. In brief, to retrieve that memory so that it can become conscious, it must be externalized in its symbolic form.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 16) Symbols are very important in the group therapy process because they can allow the trauma to surface through a safe avenue and allow the child to work through it. “Symbols express and represent meaning. Meaning helps provide purpose and understanding in the lives of human beings. Indeed to live without symbols is to experience existence far short of its full meaning.” (The Sacred Tree, 1984, p. 8) The fourth variable is activating stress within the system. Whittaker “used his own anxiety and affect to facilitate movement, believing that the therapist's internal experiences belonged to the therapy process. (Mitten and Connell, 2004, p.6) I believe this could be used when the group feels like it is growing stagnant. An avenue that can be explored would be to ask the participants what life would be like if they continued on the path they were on. If the trauma they have experienced was allowed to fester inside of them, how would they cope? I would then share my feelings with them on how I would react. By activating the stress within them, by showing them what may happen if their trauma is not treated; it may give them the drive to keep going. The fifth variable is creating a symbolic experience. Whitaker did this by “amplifying roles to provide experiences for the family and then quickly moved out.(Mitten and Connell, 2004) As part of the group therapy, role-playing will be integrated. The children will role play each of the roles: the abusive parent, the abused parent and the child. Following each role-play, the characters will discuss how they felt in their role. The last variable is moving out of the system. “Whittaker stressed the need to inform the family as a therapist you won't be a lonesome mother. He would introduce bits of his real world by talking about new projects he was working on, a trip he was planning with his own family, or an encounter with another family.” (Mitten and Connell, 2004, p. 8) The group therapy will be a set number of weeks. The children will be aware of the fact that the group is ending and everyone's life will move on. This idea of “moving on” will be stressed and repeated throughout the second half of the group sessions By using symbolic-experiential therapy and combining the Life model and ecological perspective, we can then achieve a holistic therapeutic program to utilize as a treatment model. There are several similarities which can be used to combine the life model of social work practice, ecological perspective, and symbolic-experiential therapy. The Summary of Concepts table summarizes the key elements of each concept. Figure 3 - Summary of Key Concepts

The prominent similarity among the three concepts is the person fitting into the environment. In the life model of social work practice it is through life processes; the ecological theory it is the life stressors; and through the symbolic-experiential therapy, it is the activation of stress. All of these concepts have one common activator, - the motivation to make a positive change. The positive change in this instance is the awareness and education of domestic violence, coping measures, and using symbolic art therapy. Using the symbolic-experiential therapy as a base, pieces of the ecological perspective and the life model of social work practice can be placed. Generating an interpersonal set by expanding the child's world (Mitten and Connell, 2004) can be combined with life processes, growth, habitat and niche and relatedness. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The second stage is creating a suprasystem by using parallel play (Mitten and Connell, 2004); this can be combined with coping measures, adaptations and modification to environment to promote well-being. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The third stage is stimulating a symbolic context by expressing memories or feelings in art form (Mitten and Connell, 2004); this can be combined with life processes. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The fourth stage is activating stress by using anxiety to facilitate movement (Mitten and Connell, 2004); this can be also combined with life processes and life stressors. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The fifth stage is creating a symbolic experience by amplifying roles in the family (Mitten and Connell, 2004), which can be combined with raising the person:environment fit. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The last stage is moving out of the system (Mitten and Connell, 2004), which can be combined with growth, competence, self-esteem and direction. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) Proposed Treatment The proposed treatment method will be in a group setting. Group settings work well with children. Groupwork reduces isolation, promotes corrective emotional experiences, and enhances interpersonal skills. (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 252) The central factor for the participants of this therapy group is they are no longer living in violent homes and are now in safe houses. The ecological theory (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) believes in the person:environment fit. If a child is still being exposed to the violence, his/her environment is still negatively affecting the person. If the home they live in now is free from domestic violence, the odds are better since they will have a non-abusive parent/guardian to support them. “Optimal candidates for group intervention are children who share similar treatment histories and who have had some previous individual intervention.” (Malchiodi, 2008, p. 253) The children in this group will have similar degrees of exposure to domestic violence and have also had some one-to-one counselling. If their histories are too different, the focus of the group will be too wide and it may lose its significance. The majority of this group will be art-focused therapy, within a group setting. “Any intervention with children who have been exposed to family violence has to provide positive, engaging sensory experiences and be developmentally appropriate to children's way of learning.” (Malchodi, 2008, p. 254) For the sake of age appropriateness, the group will be geared to children from ages seven to twelve. Basic Group Therapy Framework The framework for the therapeutic group will be the medicine wheel. “The medicine wheel is an ancient symbol used by almost all the Native people of North and South America. There are many different ways that this concept is expressed. The medicine wheel can be used to help us see or understand things we can't quite see or understand because they are ideas and not physical objects.” (The Sacred Tree, 1984, p. 9) The combination of the symbolic-experiential therapy, Life Model of social work practice, and the Ecological theory's content will be categorized and applied to this framework. “The medicine wheel can be used as a model of what human beings can become if they decide and act to develop to their full potential. Each person who looks deeply into the medicine wheel will see things in a slightly different way.” (Sacred Tree, 1984, p. 35) Figure 4 – Group Therapy Process for Children Who Have Witnessed Domestic Violence

(Wabie, 2009) The process of the therapy will be knowledge, symbolizing and experience, reapplication to self, and the application of knowledge to individuals, groups and communities in the child's life. “The medicine wheel is a symbolic tool that helps us to see the interconnectedness of our being with the rest of creation.” (Sacred Tree, 1984, p.41) This is recognizant of the ecological theory which makes clear the need to view people and environments as a unitary system within a particular cultural and historical context. Both person and environment can be fully understood only in terms of their relationship, in which each continually influences the other within a particular context. (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The ideas parallel each other. Using the medicine wheel is similar to using the ecological perspective with the life model of social work practice. The four aspects of the medicine wheel are the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. One more important aspect of the wheel is volition (Sacred Tree,1984, p. 15) which works with all areas and is interpreted as potential. In the life model of social work practice, it speaks of “1) people's strengths, their innate push toward health, continual growth and release of potential; 2) modifications of environments, as needed, so that they sustain and promote well-being to the maximum degree possible, and 3) raising of the level of person:environment fit for individuals, families, groups and communities.” (Germain and Gitterman, 2005) The similarity is the volition to acquire these things as they are there for us to have, if we want it. Another area that works well with the vision of the medicine wheel is the third stage in the symbolic-experiential therapy, which is “stimulating a symbolic context.” ((Mitten and Connell, 2004) Preface to Group This is a proposed arts-based therapeutic group for children (aged 7-12) who have been witnesses to domestic violence. It includes parts of Carl Whitaker's symbolic-experiential therapy (Mitten and Connell, 2004), the life model of social work practice and ecological perspective (Germain and Gitterman, 2005). The process is framed on a medicine wheel to incorporate a holistic approach and to symbolize the balance each phase has with the other. The area in which this proposed group will take place will be private, yet informal. There will be an area for tables and chairs, but also an area to sit on the floor where most of the group work will be done. An arts table will be set up, a small area to relax, and a snack area for the participants. Before, during and after the group there will be a counsellor available for any child who needs to talk further. Since these children have experienced domestic violence, the group should take into account the possible occurrence of re-traumatization of the children. Unforeseen issues may arise in group, so there will be two group facilitators in case of an emergency. One facilitator can stay with the group, while the issue is being dealt with. A talking stick will be incorporated into the group discussions to assist the group with understanding we should respect the person talking. A talking stick, feather or rock is used in the Native culture to ensure the person who is speaking and holding the rock obtains everyone's attention. Phase One – Knowledge

Week Two – Learning About Feelings / Expressing Feelings

Week Three – What is Domestic Violence? How Does It Affect Us?

Phase Two – Symbolic Experience

Week Five – Exploring Family Roles / Role Playing with Puppets

Week Six – Understanding Symbols / Creating Our Own Stories Through Art

Phase 3 – Application to Self

Week Eight – Changing the End of the Story / Living Now

Week Nine – How to Deal With Anger / How to Deal With Stress

Phase Four – Application of Knowledge

Week Eleven – Self Care Using the Medicine Wheel / Personal Safety

Week Twelve – What Have We Learned? / Family Time

Summary Further areas of study can include incorporation of child development phases, how being witness to domestic violence affects them, study varying degrees of domestic violence witnessed by these children and create a measuring tool to record the degrees and also have a concurrent group running for the abused person. Further areas of study can include incorporation of child development phases, how being witness to domestic violence affects them, study varying degrees of domestic violence witnessed by these children and create a measuring tool to record the degrees and also have a concurrent group running for the abused person. About the Author References Bopp, J., Bopp, M., Brown, L., & Lane, P. (1984) The Sacred Tree. Lethbridge, Alberta: Four Worlds International Institute for Human and Community Development. Connell, G., Mitten, T., & Bumberry, W. (1999) Reshaping Family Relationships, The Symbolic Therapy of Carl Whitaker. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. Edleson, J.L. 1999b. “Children’s witnessing of adult domestic violence”. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Vol. 6: 526-534. Fantuzzo, J.W., Depaola, L.M., Lambert, L., Martino, T., Anderson, G., and Sutton, S. 1991. “Effects of interparental violence on the psychological adjustment and competencies of young children”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Vol. 59: 258-265. Gerwitz, A., & Edelson, J.L. (2004). Young children’s exposure to adult domestic violence: The case for early childhood research and supports (Series Paper #6). In S. Schecter (Ed.), Early childhood, domestic violence, and poverty: Helping young children and their families (p. 1-18). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa School of Social Work. Gil, E. (1991). The healing power of play. New York: Guilford Press. Klorer, P. (2000). Expressive therapy with troubled children. Northvale, NJ: Aronson. Mitten, T. J., Connell, G.M. (2004) Journal of Marital and Family Therapy October 2004,Vol. 30, No. 4, 467–478 The Core Variables of Symbolic-experiential Therapy: A Qualitative Study. Previous article: SUCCESS! Play Life to Win Next article: Do you know what your kids are doing online? |

||||||||||

| Download PDF version. To change your subscription or obtain print copies contact 416-987-3675 or webadmin@oacas.org |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||